Frost School of Music dean traveled to Cuba to engage with young Cuban music students.

From reggae and calypso, to salsa and son, each Caribbean nation boasts unique musical styles that fuse indigenous, African, European and American elements. Music is a source of cultural and national pride throughout the Caribbean region, and its many styles are readily identifiable by others around the world.

The Frost School of Music’s Dean Shelton Berg is well versed in Caribbean musical styles. He traveled to Havana, Cuba, in early 2016 as part of an arts education travel symposium.

“Cuba has produced some of the world’s finest classical, jazz and Afro-Cuban musicians of the past century,” says Berg. “Musicians in Cuba seem to be thriving, and are eager to welcome visiting musicians from America.”

While Cuban musicians have, in recent years, freely traveled and interacted with their counterparts in Europe, Russia, Canada and South America, and have performed in the United States as visas were made available, for decades it was rare for Americans to visit Cuba except on some government approved cultural tours. The process is easier now with loosened travel restrictions after renewed diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba.

Berg says he decided to visit Cuba when a group of donors expressed interest in going, and asked him to curate their experience.

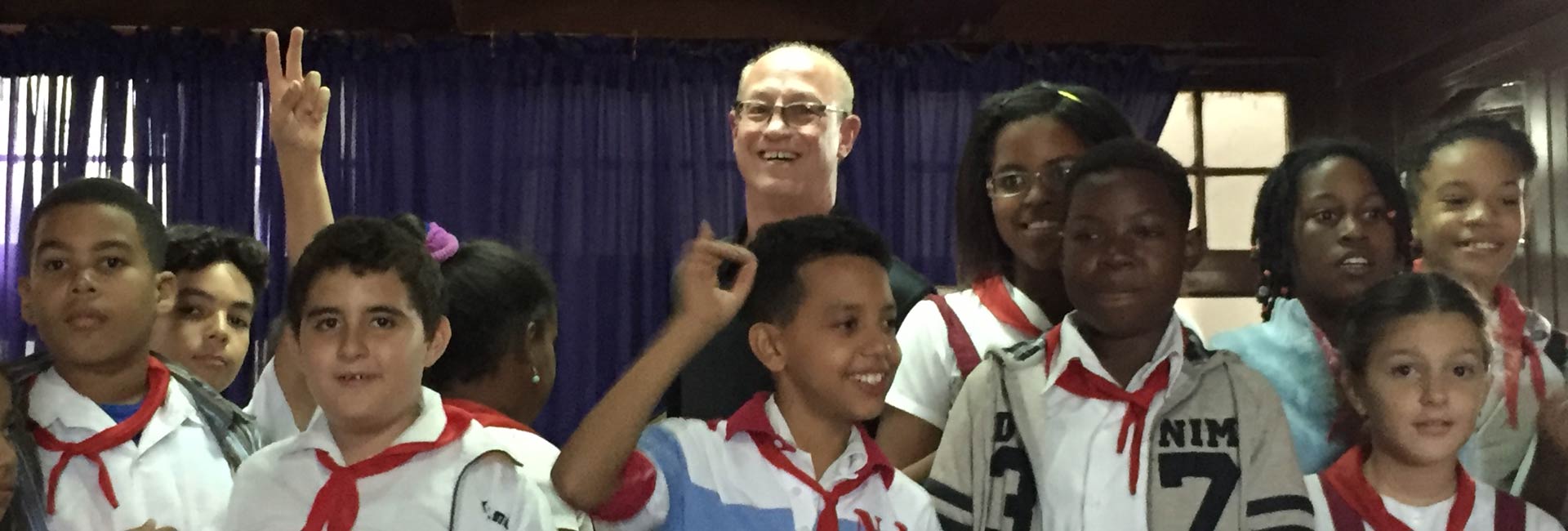

About the Photo

In 2016, UM Frost School of Music Dean Berg and guests visited the Manuel Saumell Elementary Music School in Havana, Cuba, where they were treated to a recital by young music students of varying ages and instruments. Photo courtesy of: Julia Berg

Join the Conversation:

Follow on

Twitter:

UM Frost School of Music, @frostschoolUM

University

of Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

“I wanted to hear and see first-hand how the Cuban music education system is faring today,” says Berg. “I was curious to learn how music is being taught, and how many children have access to music instruction across the country.”

The Frost School has strong connections to the island that lies less than 300 miles away.

“Several Frost music faculty such as the late Rosalina Sackstein, who was a formidable pianist and teacher, and Santiago Rodriguez, a ‘Pedro Pan’ kid that ultimately became a Van Cliburn (International Piano Competition) winner, were both born in Cuba but left during the Cuban revolution,” says Berg.

“Two recently hired faculty, pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba and percussionist Dafnis Prieto, received their musical training in Cuba and then emigrated to the United States in the late 1990s,” he adds.

The group’s tour began at a recently restored town square in Old Havana, near Calle de Los Mercaderes, renovated through a new type of public-private partnership.

“We learned from an architect that three buildings a day collapse in Havana,” Berg says. “Hopefully these types of partnerships will help preserve some of the historic buildings.”

In the square, street musicians were playing guitars and singing for tips. One offered a guiro-like instrument to Frost visiting committee member Gregg Field, a drummer and producer. It was a quijada—the dried jawbone of a donkey—its teeth rattling when hit and scraped with a stick.

The next stop was at the Manuel Saumell Elementary Music School, a Tudor-style building located in the neighborhood of Vedado where students between the ages of seven and ten receive musical instruction on piano, violin, saxophone and other instruments, as well as study music theory. A group of students would be performing for the American guests. The school is named for Manuel Saumell Robredo, a 19th century Cuban composer who added “creolized” elements to his classical compositions and is often credited as being the founder of the Cuban nationalist musical movement.

The elementary school students audition to attend the school, and travel there from a variety of municipalities in the nation’s capital. Many go on to study at the Amadeo Roldan National Conservatory, named for a violinist and composer who incorporated Afro-Cuban rhythms into his symphonic pieces in the late 1920s.

The school’s recital hall is a long and narrow room with high ceilings and a stage positioned at one end with a grand piano. Sunlight filters through diamond grille-patterned windows and a skylight above. Heavy leather-covered wooden chairs were set up in rows, the floor tiled in a black-and-white checkerboard pattern.

The audience was treated to a concert by students of varying ages, beginning with a solo by a young violinist, progressing to a talented junior high-aged pianist and culminating in a performance by a choir of about 25 girls and boys.

The younger students were dressed with short-sleeved white shirts, and small red scarves tied in front; girls wore maroon skirts with suspenders and the boys sported maroon shorts.

The tour guide explains that musical instruments and supplies, such as violin and guitar strings, are in short supply and says that donations would be appreciated.

The school principal then invited Dean Berg to play the piano for the students. After he finished, the students clamored around the piano, asking him to perform again. He suggested they perform a song together, and the children chose “Guantanamera.”

A pair of bongos emerged from somewhere, and a smiling boy sporting a striped t-shirt with “NY” on the front made his way to the head of the crowd, and set up a groove. Field joined in, playing with his hands on a tabletop. Smiles erupted when they were done, and students crowded around Berg and Field, asking for autographs.

“It is a musical moment I will always treasure,” says Berg. “Music is amazing. We went from strangers to friends in a matter of minutes. Goodwill was flowing both ways.”

The principal then cued the students to return to their choir set up, and they sang a patriotic song with the refrain “La Revolución” that extolled the virtues of their national heroes.

Berg talked afterward with several of the school’s teachers, who had been trained in a similar manner as their students, learning classical music as well as other styles.

(Story continues after photo gallery)

“They told me that the education system in Cuba is set up to provide all boys and girls with music instruction, and to help them develop their skills to the very best of their ability,” Berg says. “Full participation in music is considered a right of childhood.”

At a night club the same night, Berg jammed with a group of local jazz musicians, comprised of a family that gives lectures on the history of Cuban jazz to tour groups like the Frost School cohort. The father plays guitar and sings songs of old, his wife is a musicologist and plays the piano, and his adult son plays the electric bass. When the lecture was done, the young bassist invited Berg to sit in, and a blaze of contemporary jazz ensued.

The cultural tour continued with visits to the studios of several visual artists, who sell their works internationally for thousands of dollars each through European galleries. This was in sharp contrast to doctors, hotel managers and other professionals who said they were paid US $20 a month, and most had a second job on the side.

“The Cuban education system appears to still include top-quality music instruction in classical, jazz, salsa and traditional styles, and young musicians find ways to perform locally for tourists, or in groups that tour outside the country,” says Berg.

“Music is a beacon of hope and a source of great pride in Cuba,” he added, “and I hope their musicians will continue to thrive well into the future.”

- JULIA BERG / UM News