Corals in Cuba, considered to be some of the most pristine in the Caribbean, may help determine how these ecosystems can survive climate change.

Andrew C. Baker, an associate professor in the Department of Marine Biology and Ecology in the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, is big on the study of the ecology and conservation of coral reefs, with particular attention to the impact of climate change on these fragile environments.

Baker sat down with UM News for a Q&A to discuss his work and upcoming projects in the Caribbean.

UM News: Why is research on coral reefs in Cuba important?

Andrew Baker: Coral reefs around the Caribbean are quickly disappearing as a result of climate change, diseases, overfishing and poor water quality. However, Cuba’s reefs are doing better than most reefs in the region, mainly due to restrictions on access and fewer local impacts. Understanding whether and how Cuba’s reefs are connected to reefs in other nearby countries is important for management because Cuba’s reefs may be important sources of larvae of many species to downstream reefs, including those in the Florida Keys. Showing that transport of ecologically or economically important species – like corals, fish or lobsters – is occurring would be a powerful incentive for other countries, including the U.S., to help Cuba protect its valuable reefs from increasing pressures as its economy and coastlines begin to develop. We are using new genomic tools to look at the genetic signatures of corals from Cuba and Florida to better understand how these populations are connected and answer the question, “Where are the corals that can help Florida’s reefs persist into the future most likely to come from?”

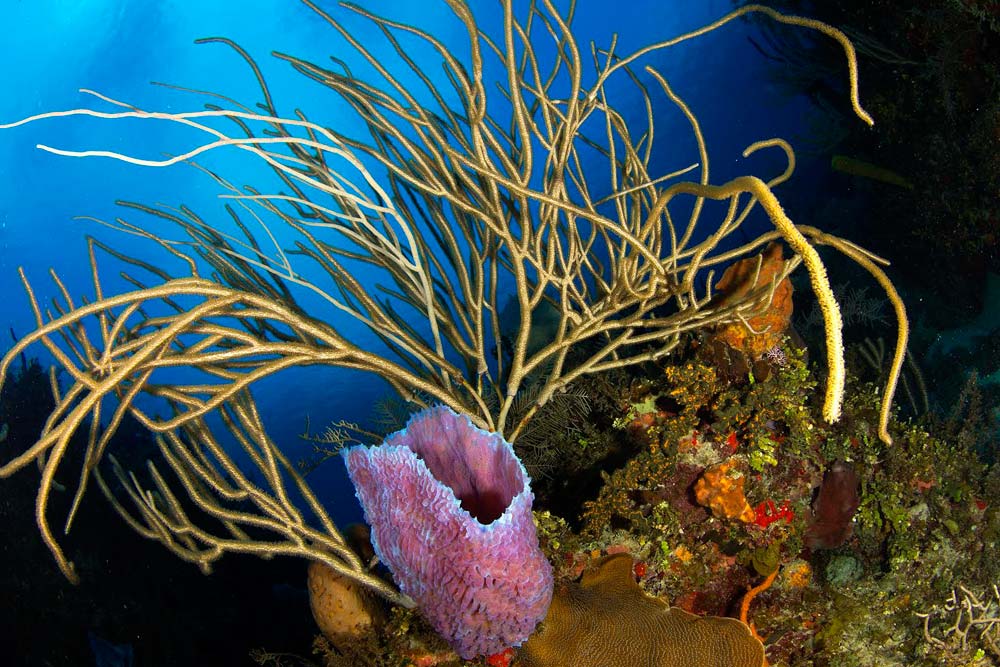

About the Photo

University of Miami researchers are working hard above and below the ocean surface to help keep coral reef ecosystems alive and healthy. Photo credit: Konrad Hughen

Join the Conversation:

Follow on

Twitter:

UM Rosenstiel School of Marine and

Atmospheric Science, @UMiamiRSMAS

University of

Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

I’m preparing for a research mission to collect samples from reefs off the Guanahacabibes peninsula at the far western tip of Cuba with my colleague (and UM-RSMAS alumnus) Fernando Bretos, of the Frost Science Museum. This is a potentially important area for the region because it lies in the Yucatan channel, directly opposite Cancun in Mexico. Water entering the Gulf of Mexico passes through this area before being funneled into the Florida Straits and entering the Gulf Stream. I’m going to find out if the corals from this area help supply Florida’s populations, or whether they come from other areas such as Mexico. I’m doing this research as part of a tri-national partnership between the U.S., Cuba and Mexico.

UM News: If corals in Florida are being killed by climate change, why does it matter that they are connected to other reefs? Can corals adapt to warming temperatures?

Baker: Corals do have some ways of adapting to warming temperatures and this area has been a focus of my research at UM for many years. However, the Cuba connection could be an important one because the south coast of Cuba in particular is much warmer than the Florida Keys and could therefore be a source of heat-tolerant corals that could help reefs in other areas deal with the threat of global warming. So, understanding how these areas are connected, and how we might potentially help increase connectivity between regions – either by cross-breeding individuals from these populations or by transplanting corals from one area to another – is a very critical area of research. Just a few years ago such ideas would have been considered extreme, but as our reefs continue to decline there are growing calls to start considering these forms of “intervention conservation.” Put another way: assisting Cuban coral immigrants to come to the U.S. could be one way of helping our reefs survive!

UM News: Wow! Is it really possible that sourcing our corals from other areas might help our reefs survive climate change?

Baker: That’s what this new research is trying to find out. It’s really a natural progression of the research I started when I first came to UM to study for my Ph.D. in 1993. Back then we were just discovering that the algal symbionts – called ‘zooxanthellae’ – that live inside corals are very diverse, and more recently we’ve found that corals that have particular kinds of symbionts are much more heat tolerant. We’re just starting a project at the new Frost Science Museum in Miami investigating ways to make corals more heat tolerant using these symbionts, and NOAA has funded a pilot project to see if this can be scaled up to help with reef restoration efforts right here in Miami-Dade County. So it’s an exciting time to be a coral researcher, even though the excitement is being fueled by the need to avert coral reefs from suffering a climate change disaster.

- ALEXANDRA BASSIL / UM News