UM anthropologist works to uncover the LGBTQ experience in the Caribbean region.

Moonlight’s Best Picture win at the 2017 Oscars was historic for many reasons, not the least of which is that Hollywood—and social science research, for that matter—historically has not blended gay and black identities in their depictions and explorations of human experience.

The lives of those who are both gay and black are of great interest to anthropologist Jafari S. Allen, who has spent the last 15 years researching these intersections of identity—not only in the United States but throughout Cuba, the Caribbean and around the world.

“We cannot understand the dimensions and dynamism of the social character of human beings without thinking about gender, sexuality, race, class and nation as they are lived—simultaneously,” says Allen, associate professor of African-American studies and anthropology and director of graduate studies for the Women’s and Gender Studies Program in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences.

New York City was where Allen’s first observations about the interplay of race, sexuality and nationality came to light. As a Ph.D. student at Columbia University, he volunteered to assist Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) with HIV awareness outreach. At GMAD, black gay men from all around the world met for politicized conversations, particularly regarding global experiences of racism and homophobia. That began to shape his intellectual curiosities.

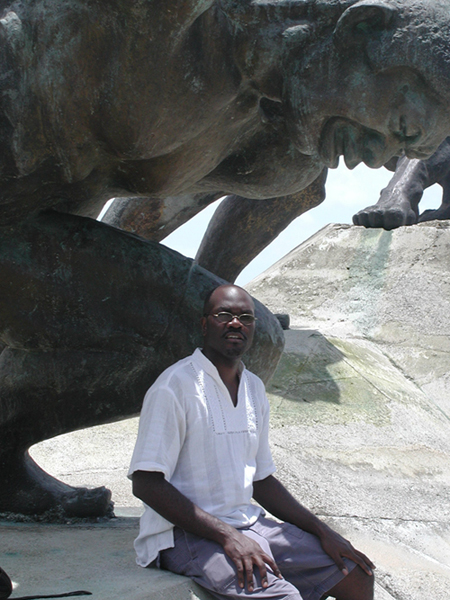

About the Photo

The Triunvirato Monument in Matanzas, Cuba sits in memory of the slave revolt at Sugar Mill Triunvirato, Matanzas, in 1843. Photo credit: Jafari Allen

Join the Conversation:

Follow on

Twitter:

UM College of Arts and Sciences, @UMCAS

University of

Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

Allen’s thesis work took him to Cuba, where he first sought to define black masculinity in the island-nation. A large proportion of the artists, intellectuals and people he interviewed also identified as LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning).

“My focus shifted as I realized I could make a bigger contribution by looking particularly at the lives and circumstances of folks whose intersectional identities were most silenced in the literature and whose stories were most instructional,” Allen recalls.

The fruit of his seven years of research in Cuba is “!Venceremos? The Erotics of Black Self-Making in Cuba,” an ethnography that explores race, desire and belonging among black Cubans in the early 21st century. The title, which translates to “We Shall Overcome?,” turns a popular revolutionary-era slogan from a statement into a question. Subverting the meaning this way calls attention to pervasive marginalization of black citizens, prejudice against sexual minorities and gender inequities in the country.

“One of the things that surprised me was that no one had ever done a project like this before, specifically that there had been only one ethnography of revolutionary Cuba written in English,” Allen says. “And the questions I was pursuing were not questions Cuban studies [as a field] had seen as important at the time. The way we look at Cuba here in the U.S. academy had been shaped by stellar scholars; however, their background and orientation produced blind spots. If they saw Afro-Cuba at all, it was only through the most folkloric understanding. Cuban studies has a lot to learn about critical race studies and feminist and queer studies taking place in various parts of the world.”

“!Venceremos?,” a finalist for the 2012 Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ literature, was the springboard for Allen’s current work, which he describes as “black queer transnationalism.” He began looking at networks of HIV/AIDS and LGBTQ activism in Latin America and the Caribbean to find organizations and places “where there is an intersectional discussion of race and gender, as well as sexuality.

“I wouldn’t want to talk about any one of these places in terms of LGBTQ issues without also grounding that in the nation’s geopolitical framework and what is happening around color and race and gender,” Allen explains.

This quest led him first to places like Brazil, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, but soon his travel trajectories landed in Nairobi, London, Bridgetown, Paris, Toronto and several U.S. cities, including Miami. Tentatively titled “There Is a Disco Ball Between Us,” Allen’s book in progress is based on more than two years of “tracing various south-south and south-north-south routes of works and bodies.”

Allen served eight years on the faculty at Yale University before joining UM in 2016. Miami has been an inspirational new home, not only for its proximity to the Americas or its plethora of Cuban, Dominican, Jamaican and Haitian food, languages and people.

“In terms of the academy, Miami is a place that understands the importance of the New World,” he says. “The Ivy League is the Old World, and the orientation is looking north across the Atlantic for inspiration. In Miami, there are so many influences that it’s hard to know where to look, but if we had to choose, it would be looking at the Global South and the U.S. South, where so much important work is happening right now.”

Allen will be spending this summer in Paris, London, and Trinidad and Tobago, where he is excited to talk to research respondents about, among other things, their reaction to Moonlight. He expects the film to resonate with black LGBTQ people particularly in the Caribbean because it captures a sensibility of Miami that’s reflective of the city’s Caribbean influences. He plans on including reactions to the film, which was adapted from the work of playwright and former UM professor Tarrell Alvin McCraney, in his forthcoming book as yet another example of the multidirectional, evolving flow of people and ideas across international borders.

“I hope this work will become a model for doing work that engages ideas as they actually emerge, flow and change from place to place as they do in real life—without the artificial boundaries of region or nation or theoretical framework,” Allen says. “The lines of lived experience are seldom straight, precise and elegantly drawn. The work should be an honest, compelling and beautiful chronicle of what black/queer looks like traveling from place to place—teaching and learning a number of lessons from which we can all draw.”

- MEREDITH CAMEL / UM News