Frost School of Music musicologist explores the impact of music within the narrative of Haiti’s cultural and religious identity.

During an all-night service in Jacmel, Haiti—known as jenn or veydenwit—worshippers raise their hands and chant upbeat lyrics to the sounds of boisterous drums and tambourines.

Select worshippers, or “heavenly armies,” begin to spin and dance themselves into a trance-like state, seemingly unaware of anyone or anything around them. The sounds and rituals of the ceremony favor traditional Haitian music and rhythms of Carnival and konpa, allowing army members to wage “spiritual warfare” to protect the congregation against Satan and demonic spirits. During the worship, no one questions the intense spiritual fight—it is understood that members are “filled”—allowing them to heal, prophesize and protect the congregation.

To some Haitians, the rituals and music of heavenly armies blur the lines between Protestant Christianity and the folk religion known as Voodoo or Vodou. According to Melvin Butler, associate professor of musicology at the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music, the perpetual fears of these independent congregations may be equivocal, at best.

About the Photo

“Heavenly army” members seen here trance dancing in Jacmel, Haiti, in 2006. Photo credit: Melvin Butler

Join the Conversation:

Follow on

Twitter:

UM Frost School of Music, @frostschoolUM

University

of Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

Butler explains that the success of the heavenly armies stems from the fact that Pentecostalism has been planted on cultural ground fertilized by the country's tumultuous military history. The term heavenly army, or lame seles, usually refers to a battalion of spiritual entities empowered by God to wage a war against evil forces. Although this battle is fought primarily in the spiritual realm, the musical worship is a form of spiritual weaponry, often calling upon God to attack demonic spirits and individuals.

Using native drums, scrapers and homemade instruments, the heavenly armies also use music to distinguish themselves from other religious groups and to express a Haitian cultural identity.

Over the past 17 years, Butler has been immersed in various aspects of Haitian culture, religion and music relating to charismatic Christianity, which is a form of Christianity that emphasizes the work of the Holy Spirit, spiritual gifts and modern-day miracles as a regular part of a believer's life. With a specific focus on Pentecostal practice within Haiti, his research has led him on many different paths, often exposing deep complexities and contradictions.

“Almost everyone is some sort of Christian in Haiti,” says Butler, as he explained the historical importance of Vodou and the shifting influence of Christianity. “When I speak to Haitians about their associations with specific denominations of Christianity, labels such as Protestant or Baptist are often misguided from the traditional sense. I am able to learn more about specific beliefs and practice by the type of music sung at their church,” he adds.

Within Pentecostal practice around the globe and in Haiti, music is imperative—serving as the vessel for the transcendence of the Holy Spirit—for divine encounters during worship. When “filled” by the Spirit, worshippers may speak in tongues or theatrically clap and dance. Though Pentecostals share similar theological beliefs as many other denominations of Christianity, the energy and intensity of their musical worship often sets them apart.

Unlike the culturally rooted rhythms found within the rituals of the heavenly armies, many Pentecostal Christians channel the musical influences of U.S. counterparts. Often incorporating keyboards and drum sets, the sounds of worship can vary from upbeat to meditative. Even within Haitian Pentecostal worship, churches are deemed as “hot” or “cold” based on the musical selection of the congregation.

These designations often add another level of complexity when attempting to signal the differences between independent heavenly army churches and organized Pentecostal congregations, even for Butler. He recalls attending service within a “hot” Pentecostal church in Jacmel, where emphasis was placed on lively musical activity, yet the Pastor frequently preached against involvement in Carnival, rara processionals, and Vodou.

“Soon into the service I realized that, theologically, the worship wasn’t what I knew as Pentecostal, but for many Haitians, the music is what defined their beliefs,” says Butler.

Even before embarking on field research in Haiti, Butler knew first-hand of the country’s internal battle with varying musical styles. As a saxophonist, he first traveled to Haiti in the early 1990s while on tour with Tabou Combo, a renowned Haitian dance band. The band's music, known as konpa, channeled the sounds of Haitian culture and native life on the island. Debates about konpa are key to understanding the divide between the musical preferences of organized congregations and independent heavenly armies. The experience would serve as Butler’s introduction to the fraught coexistence of popular music and charismatic worship within Haiti.

Even on his most recent research trip in 2015, to Port-au-Prince and Jacmel, Butler was continuously confronted with the balance of shared cultural identities within Pentecostal Haiti. Aside from the transcendent fight through music and worship, the independent congregations and heavenly armies battle to maintain a place within Haitian culture and religion.

Generally equipped with a recording device for research when attending services, Butler notes that “there were lots of times when recording a piece of music did not provide all of the answers, nor did it offer a complete picture of what the experience of these kinds of rituals entail."

"Music is but one piece—albeit a vital one—of a broader constellation of activities that give worship services meaning and significance,” he adds.

Often stigmatized and misunderstood, Vodou's narrative is further nuanced by Butler's research. By exploring the relevance of musical sounds as the catalyst for worship and cultural expression, Butler sheds important light on the diversity and complexity of religious worship in Haiti.

- JENNIFER PALMA / UM News

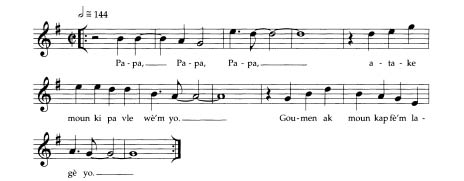

Sound Clip: Papa Papa Papa

Father, Father Father, attack those who despise

me.

Fight against those who make war.

Recorded in Jacmel, Haiti, in 2001, “Papa, Papa, Papa,” is from a "heavenly army" congregation, and the lyrics are based on Psalm 35:1. This piece as an example of spiritual warfare through music and calls upon God to “attack” (atake) evil spirits and individuals of misfortune. The chorus is typically repeated several times as a way of building musical intensity and emphasizing the meaning of the text. The song is sung most often, says Butler, during the loudest and most intense moments of worship services, when singing and bodily movement are highly energetic and emotional.

Sound Clip: Pa ba Satan glwa

The sound clip is of a short song entitled, "Pa bay Satan glwa" ("Don't give Satan glory"). Butler recorded it at a mainstream (i.e., not a heavenly army-type) Pentecostal church in Jacmel, Haiti, in 2000. Other than a faint guitar, there are no instruments other than the congregants' voices and handclapping. The handclapping, says Butler, provides an excellent sense of the rhythmic accompaniment one might hear a percussionist or drummer play.