Chinese associations and secret societies in Cuba have deep

sociocultural and religious roots back to eighteenth century

China.

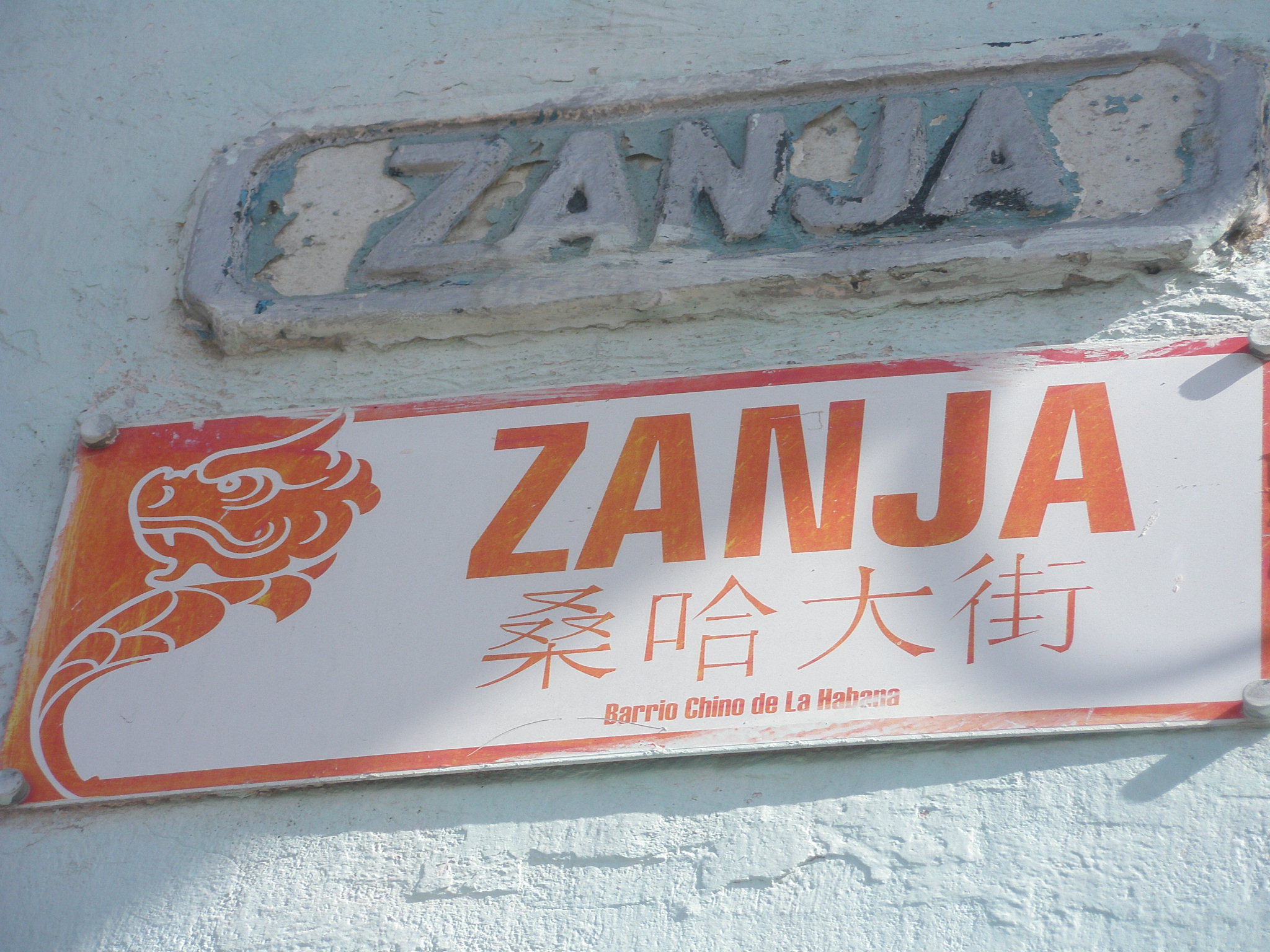

Havana’s Chinatown—El Barrio Chino de la Habana—is the oldest Chinatown in the Caribbean and is a major tourist draw. It spans approximately 45 square blocks of living quarters, economic ventures, Chinese associations, and plenty of restaurants serving both traditional Chinese food and comida criolla, Cuban creole cuisine.

I am Martin Tsang and, as a post-doctoral associate with University of Miami Libraries, I’ve studied the influence of Chinese culture in Cuban society, including the evolution of Chinese neighborhoods and social organizations in Havana and across the island since the arrival of the first Chinese indentured servants in the mid-nineteenth century.

Havana’s Chinatown has many Chinese mutual aid associations, or huiguans. Initially, huiguans were established to provide social welfare assistance to Chinese bachelors in Cuba. In the decades following the 1847 arrival of the first Chinese indentured servants, the immigrants were quickly plugged into Cuban society through their affiliation with one or more of these associations, which provided orientation, bureaucratic and legal aid, translation services, help with letter writing, temporary lodging, credit and mutual aid, and emergency funds. Since their inception, the associations have been sources of historical narratives and genealogies, and sites of Chinese community activity, recreation and education, promoting cultural and festive celebrations of the Chinese lunar calendar.

Over the decades, the associations evolved. Newspapers ran sensationalist reports of El Barrio Chino and singled out the associations for suspected links with the black market, Chinese politics, gang warfare, gambling, opium and prostitution. These reports heightened public suspicion of the Chinese as clannish and impenetrable, and greatly furthered sinophobia, culminating in a nationwide closure of Chinese associations around 1967.

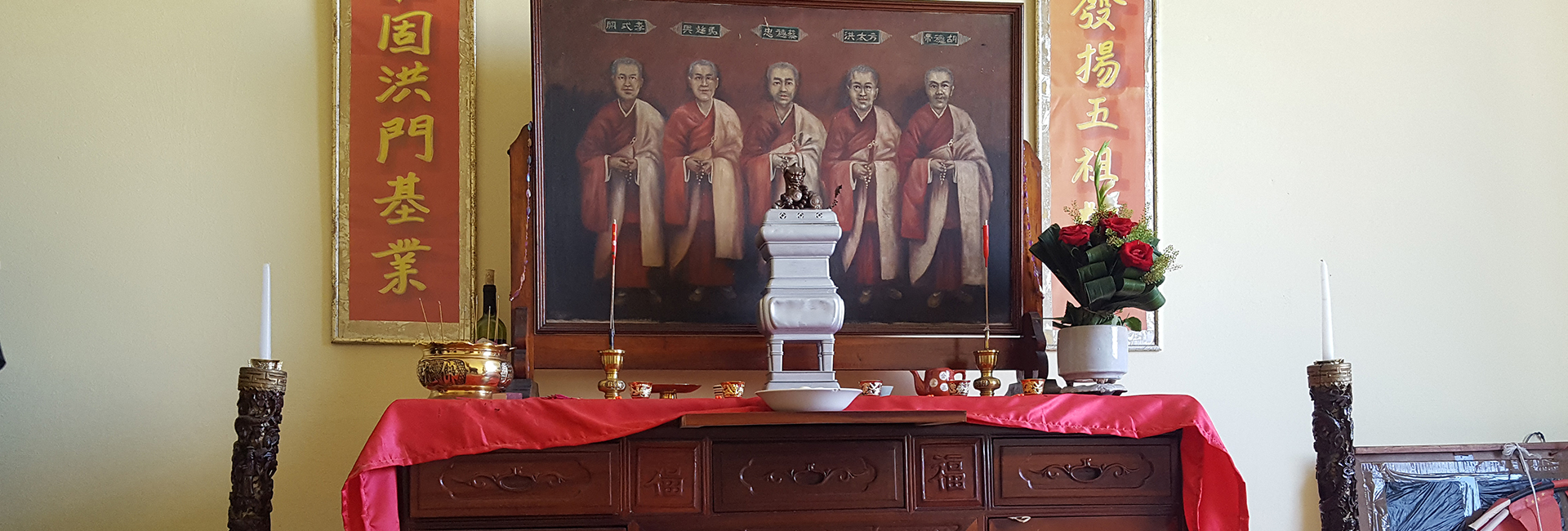

About the Photo

Private altar for the five Shaolin monks who are credited as founding the “secret society” Min Chih Tang (MCT). Photo credit: Martin Tsang

Join the Conversation:

Follow on

Twitter:

UM Libraries, @UMiamiLibraries

University of Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

For 25 years, the associations were forced underground to avoid public scrutiny. They’ve since re-emerged as government-licensed organizations with stated goals of public assistance and education. Though suffering from being misunderstood, these associations are deemed lifelines for the elderly Chinese community in Cuba today.

Between 1900 and 1929 there were 35 state-registered Chinese associations in Havana. Today there are 13 associations operating in Havana’s Chinatown, with some of these organizations having regional branches in provinces throughout the island.

(Story continues after photo gallery)

One association is Havana’s National Association Chee Kung Tong, which is commonly referred to as Min Chih Tang (MCT). The Havana lodge—or logia, how members refer to their organization—has a restaurant and, above it, are residences and a shrine room where ceremonies and celebrations take place. Society members pay 12 Cuban pesos (approximately 50 US cents) for annual membership and they receive breakfast and lunch every day of the year. In the great hall, with its mural of the Great Wall of China, members can watch Chinese language movies and read newspapers and books or socialize.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, associations such as these boasted membership in the tens of thousands. The MCT currently has about 200 elderly members, men and women, and mainly second and third generation Chinese-Cubans.

The group was founded in Cuba by Chinese immigrants in early 1887, but its roots stem much deeper in China, from the early 1760s, as an underground fraternity whose motive was to overthrow Manchu rule (also known as Qing) and fight for the reinstatement of the Ming Dynasty.

Brotherhoods such as the MCT, also called Hungmoon, thus became synonymous with secrecy and were established in China on the principles of loyalty and fraternity, operating covertly, and branching out from southern China to form a vast transnational network wherever large populations of Chinese immigrants (Huaqiao) are present overseas.

The Cuban MCT and its Chinese predecessor incorporate religious traditions and both are referred to as the Heaven and Earth Society, where Heaven is viewed as the father, Earth as the mother, and members are brothers and sisters. Heaven, earth, and humanity, or brethren, form the three most important and fundamental elements of the organization and these are echoed in its rituals, construction of altars, code of practice and iconography.

The MCT’s iconography, for example, incorporates symbols of European Freemasonry, especially the square and compass with the letter “G,” and this is often combined with Chinese-derived Hungmoon symbols, such as triangles representing the trinity of heaven, earth, and humanity, and flags in five colors representing the five Shaolin monks who established the organization.

Visiting Havana’s Chinatown, one is most likely to see a shrine of Guan Gong, known in Cuba as San Fan Con. He is the deity that MCT members most venerate, and initiations take place before his image.

Recent research into Chinese secret societies has explored their linkages to European and North American Freemasonry practices. Chinese Masonry and European Freemasonry are similar in form. They both require oath-taking by their members, have highly ceremonial and ritualized meetings, use specialized or secret language, have a strict hierarchical structure, and have legends and narratives that give the membership a rationale for existing.

Contemporary Heaven and Earth societies in Asia, colloquially called Triads because of their tripartite structure and symbolism, have gained a reputation of being criminal, having originated as a perceived threat to British rule in colonial Hong Kong. As such, the outlawed Triads have nothing in common with the practices of the Cuban MCT.

The Min Chih Tang and the other twelve associations that are still operating in Cuba are accustomed to adapting to a constantly changing social and cultural sphere. Stepping into the world of the Min Chih Tang, or any of the other associations in the island today, helps us to understand the many parallel histories of Cuba’s immigrants over the centuries, many of which are not well known. What will become of this “secret society” in the future and the role it will play in Chinese-Cubans’ lives remains to be seen.

- Martin A. Tsang / UM News